The Development of Mahayana Buddhism

Additional Buddhist practices and teachings began to appear in a wide range of scriptures from the early centuries CE.

These further developments in thought and practice gradually evolved into what is called Mahayana, the Great

Vehicle. ... An early Mahayana scripture, the Lotus Sutra,

defended its seemingly innovative ideas by claiming that

earlier teachings were skillful means for those with lower

capacities. The idea is that the Buddha geared his teaching to his

audience, and that his teachings were presented in different ways and at different levels of completeness in accordance with the readiness of his audience to understand them. ...

The Lotus

Sutra and other new Mahayana scriptures also taught that there was a higher

goal than the arhant’s achievement of liberation, namely, to aspire to become a bodhisattva.

Theravada Buddhists use the term bodhisattva to refer to the Buddha in

his past lives and up to the time he attained enlightenment. Mahayana

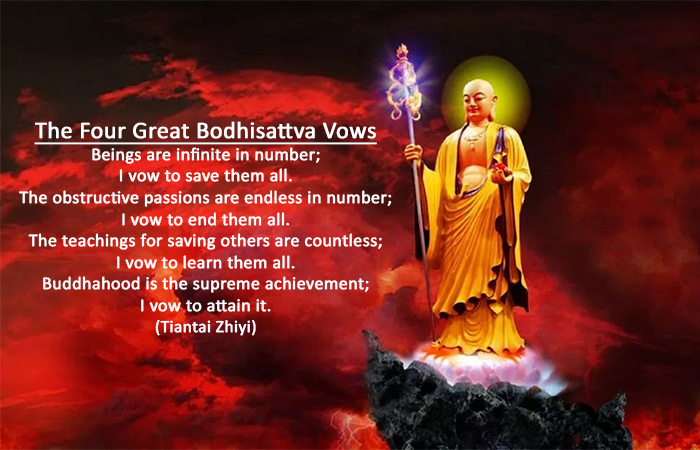

Buddhists speak of the bodhisattva as a being who has taken a vow

to become fully enlightened in the future — a fully awakened Buddha —

and who will assist others in their liberation as they work to complete

their vow. The Lotus

Sutra says

that all beings have the capacity for Buddhahood and are destined to

attain

it eventually. Both monastics and laity are urged to take the bodhisattva vow and work to become fully enlightened. ...

The concept of the selfless bodhisattva is not just an ideal for

earthly conduct; numerous bodhisattvas are believed to be

present and available to hear the devotees’ petitions. ... The most popular bodhisattva in East Asia is Avalokiteshvara (known as Guanyin in China, Kannon in Japan), who symbolizes compassion and extends blessings to all. Although he is depicted as male in India, the

Lotus Sutra says that this bodhisattva takes whatever form is needed to

help others, and lists thirty-two examples. In East Asia, Avalokiteshvara

is typically depicted as female, often as the bestower or protector of young children. (Living Religions, 155-7)

Key Concepts of Mahayana Buddhism

|

I. The Bodhisattva Path

The first characteristic notion found in developed Mahayana is the view that a Buddha, rather than an arhat,

is the person who can be of most help to people who are suffering and

in need of liberation. To achieve this condition of Buddhahood, one

needs to follow the Bodhisattva Path. This bodhisattva life begins with

what is called the “arising of the thought of Awakening,” or bodhicitta. This bodhicitta

is really the altruistic desire, or heartfelt aspiration, to attain

Buddhahood so that one can help others gain freedom from suffering. (BIBE, 117)

II. The Perfection of Wisdom

II. The Perfection of WisdomA second characteristic of Mahayana teaching is the notion of a “higher wisdom” (prajnaparamita) realizing “emptiness” (sunyata).

This notion has to do with the awakened experience of the Buddhas and

bodhisattvas. For Mahayana, what one experiences with awakened

consciousness is that all the “factors of existence” (dharmas), which we have seen were so carefully analyzed in the Abhidharma Pitaka, are “empty” (sunya)

of existing independently, or “on their own.” ... This is another way of

saying what the Buddha himself taught, namely, that all things arise

dependently. To experience this dependently arisen nature of

things — their “emptiness” of independence — is the core of wisdom

experience according to Mahayana. It is this profound wisdom realizing

emptiness that, coupled with a compassionate motivation to save all

living beings, furthers one’s Great Journey to the goal of Buddhahood. (BIBE, 117)

Om!

Praise to the blessed and noble perfection of wisdom! The noble

Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva was moving in the deep journey of the

perfection of wisdom. When he looked down at the Five Aggregates, he

saw that they are empty of own-being.

Here, O Sariputra, form is emptiness, emptiness is form. Form is

not different from emptiness, emptiness is not different from form.

What is form is emptiness, what is emptiness is form. The same is true

for sensations, perceptions, mental formations and consciousness.

Here, O Sariputra, all dharmas are characterized by

emptiness; they are neither produced nor cease, they are neither

defiled nor pure, they are neither deficient nor complete. ... Therefore,

one should know the great mantra of the perfection of wisdom, the mantra of great knowledge, the unsurpassed and unequaled mantra, the mantra that allays all duhkha — it is true, for there is nothing lacking in it. By the perfection of wisdom is this mantra spoken. It is the following: Gone, gone, gone beyond, utterly gone beyond; Awakening; O joy! (BIBE, 122)

|

A

third characteristic of Mahayana teaching concerns the nature of

consciousness. We have seen that one view of consciousness found in

early Buddhist texts teaches that the mind is naturally pure and clear,

having been stained by mental defilements. While in Mahayana there are

many and sometimes conflicting notions concerning consciousness, we

find a similar strand of thought. It claims that consciousness, prior

to being affected by defilements, is the luminous clarity nirvanic

status of enlightened Buddhahood. This pure luminosity as the true

essence of consciousness gives people the potential for Buddhahood. But

ordinary conscious life generates conceptualizations and other mental

formations that frustrate this potential. In the end, it is the mind

that enslaves people in a life that is untrue and unsatisfying (duhkha); and it is also the mind that can set people free. (BIBE, 118)

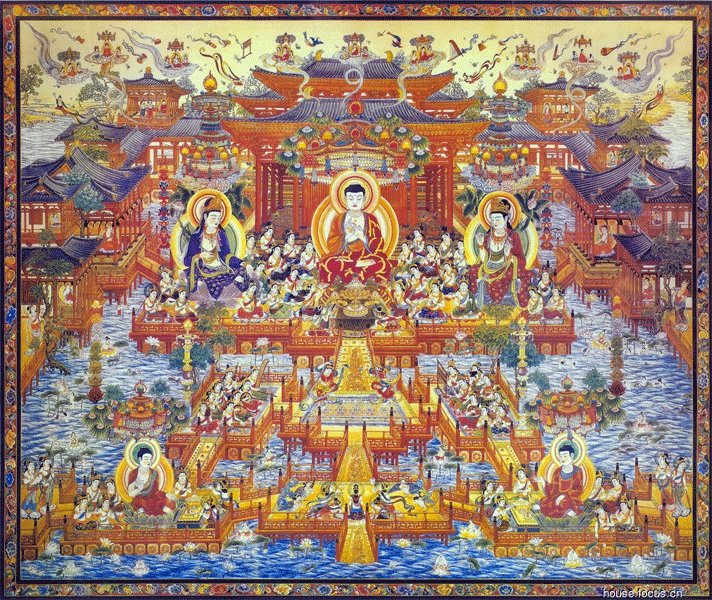

IV. Buddha Realms IV. Buddha RealmsFinally,

the fourth characteristic notion has to do with the nature of

Buddhahood, the goal of the Bodhisattva Path. While the early Buddhist

texts claim that the cosmos includes realms of hells, ghosts, gods,

and Brahma beings,

Mahayana expanded this vision of the cosmos by claiming that it also

contains countless Buddhas residing in Buddha realms. In following the

Bodhisattva Path, one can be reborn in one of these realms, where one

can progress toward Buddhahood under the guidance and with the

blessings of the Buddha of that realm. When one attains Buddhahood, one

will also create a Buddha realm from where one will help others

throughout the cosmos. In the meantime, one can receive guidance and

blessings in this world, as well as visualize these “celestial” Buddhas

and their realms and the advanced bodhisattvas that abide in them in

ways that are spiritually transforming. These Buddhas and advanced

bodhisattvas develop special skillful means (upaya)

that they use to appear in the many world systems of the cosmos in

order to help other beings become free from suffering and progress in

the journey to Awakening and Buddhahood. (BIBE, 118)

Two Approaches to Mahayana

Self Power & Other Power

|

|

“Self-Power”

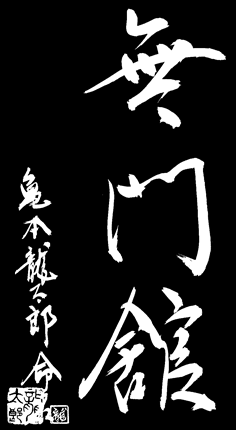

The Chan/Zen Tradition

|

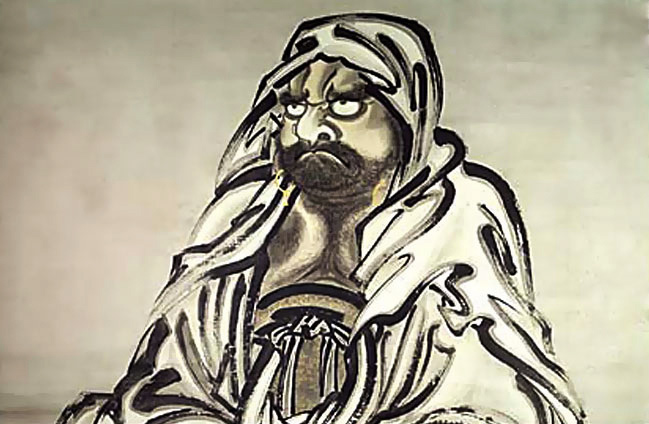

Buddhism

was transmitted from India to China beginning around the first century

CE and thence to Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. The major schools of East

Asian Buddhism are part of the Mahayana branch. Many of these schools

have also absorbed elements from other East Asian religions, such as Daoism, Korean shamanic practices, and Shinto. ... Around the fifth century CE, according to tradition,

a South Indian monk named Bodhidharma traveled to a monastery in

northern China, where he reportedly spent nine years in silent

meditation, “facing the wall.” He became recognized as the first

patriarch of the radical path that came to be called Chan Buddhism,

from the Sanskrit word dhyana,

meaning meditation. Although traditional accounts of Bodhidharma’s life

and contributions may not be completely factual, they illustrate the

emphasis on meditation and direct insight that characterize the Mahayana school of Chan

Buddhism, which became the most successful form of Buddhism in China. (Living Religions, 160) Buddhism

was transmitted from India to China beginning around the first century

CE and thence to Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. The major schools of East

Asian Buddhism are part of the Mahayana branch. Many of these schools

have also absorbed elements from other East Asian religions, such as Daoism, Korean shamanic practices, and Shinto. ... Around the fifth century CE, according to tradition,

a South Indian monk named Bodhidharma traveled to a monastery in

northern China, where he reportedly spent nine years in silent

meditation, “facing the wall.” He became recognized as the first

patriarch of the radical path that came to be called Chan Buddhism,

from the Sanskrit word dhyana,

meaning meditation. Although traditional accounts of Bodhidharma’s life

and contributions may not be completely factual, they illustrate the

emphasis on meditation and direct insight that characterize the Mahayana school of Chan

Buddhism, which became the most successful form of Buddhism in China. (Living Religions, 160)

|

Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind

Shunryu Suzuki

For

Zen students the most important thing is not to be dualistic. Our

“original mind” includes everything within itself. It is always rich

and sufficient within itself. You should not lose your self-sufficient state of mind. This does not mean a closed

mind, but actually an empty mind and a ready mind. If your mind is

empty, it is always ready for anything; it is open to everything. In

the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities; in the expert’s mind

there are few. (Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, 21)

What is our "original mind"?

If the "original mind" is our true mind, then how can it be lost?

How does having an "empty mind" allow us to reconnect with this "original mind"?

|

The Koan

The Koan

The word Koan

or Ko-an comes from the Chinese term kung-an, literally “public

notice,” or “public announcement.” ... Basically a Koan is a paradoxical utterance used in Zen as a

center of concentration in meditation. The paradoxical nature of Koans

is essential to their function: The attempt to break down conceptual

thought. Koans are constructed so that they do not succumb to conceptual

analysis and thereby require a more direct response from the meditator. (the-wanderling.com/mu.html)

A monk asked Joshu:

“Does a dog have Buddha Nature?”

Joshu replied, “Mu!”

Joshu replied, “Mu!”

... concentrate your

whole self, with its 360

bones and joints and 84,000 pores, into Mu making your whole body a

solid lump of doubt. Day and night, without ceasing, keep digging

into it, but don’t take it as “nothingness” or as “being”

or “non-being.” It must be like a red-hot iron ball which you

have

gulped down and which you try to vomit up, but cannot. You must

extinguish all delusive thoughts and feelings which you have cherished

up to the present. After a certain period of such efforts, Mu

will come to fruition, and inside and out will become one

naturally. You will then be like a dumb man who has had a

dream. You will know yourself and for yourself only.

Then all

of a sudden, Mu will break open and astonish the heavens and shake the

earth. It will be just as if you had snatched the great sword of

General Kan. If

you meet a Buddha, you will kill him. If you meet an ancient Zen

master, you will kill him. Though you may stand on the brink of

life and death, you will enjoy the great freedom. In the six

realms

and the four modes of birth, you will live in the samadhi of innocent

play.” |

|

Mumon’s Final Verse

Dog! Buddha nature!

The perfect manifestation, the absolute

command;

A little “has” or “has not,”

And body is lost! Life is lost!

|

So ... what did the Enlightened Cat

say to the Buddha Nature Dog?

DOUBLE-CLICK BELOW FOR ANSWER

DOUBLE-CLICK BELOW FOR ANSWER

MEW

|

|