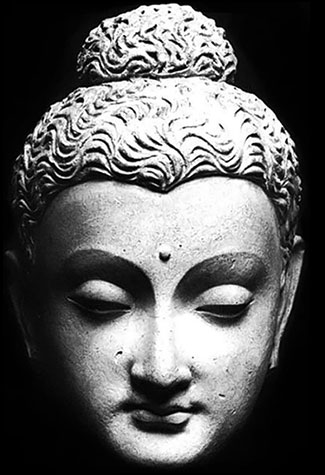

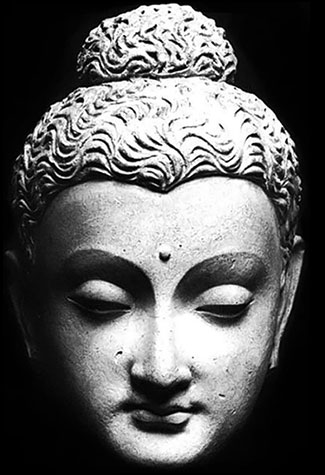

The

one who became the Buddha

(a generic term meaning “Awakened One”) was reportedly born

near what is today the border between India and Nepal. He was named

Siddhartha Gautama, meaning “wish-fulfiller” or “he

who has reached his goal.” It is said that he lived for more than

eighty years during fifth century BCE, though his life may have

extended either into the late sixth or early fourth century. His

father was apparently a wealthy landowner serving as one of the

chiefs of a Kshatriya clan,

the Shakyas who lived in the foothills of the Himalayas. The family

name, Gautama, honored an ancient Hindu sage whom the family claimed as

ancestor or spiritual guide.

His mother, Maya, is said to have given birth to him in the garden of Lumbini near Kapilavastu [in contemporary Nepal]. The

epics embellish his birth story as a conception without human

intercourse, in which a white elephant carrying a lotus flower entered

his

mother’s womb during a dream.

He is portrayed as the

reincarnation of a

great being who had been born many times before and took birth on earth

once again out of compassion for all suffering beings. According to legend, the child was raised in the lap

of

luxury, with fine clothes, white umbrellas for shade, perfumes,

cosmetics, a mansion for each season, the company of female musicians,

and a harem of dancing girls. He was also trained in martial arts and

married to at least one wife, Yashodhara, who bore a son.

Despite this life

of ease, Siddhartha was reportedly unconvinced of its value. As

the legend goes, the gods arranged for him to see “four sights” that

his

father had tried to hide from him: a bent old man, a sick person, a

dead person, and a mendicant seeking lasting happiness rather than

temporal pleasure.

Seeing the first three sights, he was dismayed by the impermanence of

life and the existence of old age, suffering, and death. The sight of

the monk piqued his interest in a life of renunciation. As a result, at

the

age of twenty-nine Siddhartha renounced his wealth, left his wife and

newborn son (whom he named Rahula, meaning

“fetter”), shaved his head and donned the coarse robe of a

wandering ascetic. He embarked on a wandering life in pursuit of a very

difficult goal: finding the way to total liberation from suffering.

Many Indian sannyasins were

already leading the homeless life of poverty and simplicity that was

considered appropriate for seekers of spiritual truth. Although the

future Buddha later developed a new spiritual path that

departed significantly from Brahmanic tradition, he

initially tried traditional methods. He

headed southeast to study with a brahmin teacher who had many

followers, and then with another who helped him reach an even higher mental state.

Unsatisfied, still searching, Siddhartha reportedly underwent six years of extreme self-denial

techniques: nakedness, exposure to great heat and cold, breath

retention, a bed of brambles, severe fasting. Finally he

acknowledged that this extreme ascetic path had not led to

enlightenment. ...

Siddhartha

then shifted his practice to a

Middle Way that rejected both self-indulgence and self-denial. He revived his

failing health by accepting food once more and began a

period of reflection. On the night of the full moon in the sixth lunar month, it is said that he sat in deep

meditation beneath a tree in a village now called Bodh Gaya,

and finally experienced supreme awakening. ... After this experience of

awakening or enlightenment, it is said that he was radiant with light. (Living Religions, 137-40)

|

Birth is suffering, old age is

suffering, sickness

is suffering, death is suffering. Involvement with what is

unpleasant

is suffering. Separation from what is pleasant is

suffering.

Also, not getting what one wants and strives for is suffering. ... [In sum,

the] five agglomerations (skandhas), which are the basis of

clinging

to existence, are suffering. (The

Experience of Buddhism, 33)

| The Buddha’s First Noble Truth is the existence of dukkha: pain,

suffering and dissatisfaction. At some time or another, we all

experience grief, unfulfilled desires, sickness, old age, phsyical

pain, mental anguish, and eventually death. We may be happy for a

while, but even when we feel happiness, it may be tinged with fear for we know that this happiness does not last. (Living Religions, 142-3) |

And what is the [second] Noble Truth

of the origination

of suffering? It is the thirst for further existence, which comes

along with pleasure and passion and brings passing enjoyment here and

there. This, monks, is the Noble Truth of the origination of suffering. (The

Experience of Buddhism,

33)

| The Second Noble Truth is that the origin of dukkha

is craving and clinging — to sensory pleasures, to fame and fortune,

for things to stay as they are or for them to be different — and

attachment to things and ideas. The Buddha taught that craving leads to

suffering because of ignorance: We fail to understand the true,

constantly changing nature of the things we crave. We grasp at things

and hold onto life as we want it to be, rather than seeing things as

they are, in a constant state of flux. (Living Religions, 143) |

And what is the [third] Noble Truth

of the cessation

of suffering? It is this: the destruction without remainder

of this very thirst for further existence, which comes along with

pleasure

and passion, bringing passing enjoyment here and there. It is

without

passion. It is cessation, forsaking, abandoning,

renunciation.

This, monks, is the Noble Truth of the Cessation of Suffering. (The

Experience of Buddhism, 33)

| The Third Noble Truth is that dukkha

will cease when craving and clinging cease. In this way, illusion ends,

insight into the true nature of things dawns, and nirvana is achieved.

One lives happily and fully in the present moment, free from

self-centeredness and full of compassion. One can serve others purely,

without thought of oneself. (Living Religions, 143) |

One

thing that is interesting about the Buddha’s statement of the Third

Noble Truth is the few words he uses in comparison to the number used

in stating the other three truths. Perhaps the reason is that the

Buddha never spoke very much about what Nirvana ultimately is. Up to

this point we have been looking at teachings of the Buddha that he

explicates at some length. Therefore, there is not a great deal of

disagreement among scholars about what those teachings entail. However,

this is not the case with Nirvana. In fact, volumes have been written

in which scholars have tried to answer the question, “What is Nirvana?”

Some claim that it is an absolute Truth. Others say it is a

transcendent metaphysical Reality. Still others argue that it is a

supermundane experience or a supreme and pure state of mind. (Buddhism: Introducing the Buddhist Experience,

50)

If there is "no soul" (anatman), then who attains nirvana (whatever "nirvana" means)?

When you open the mind to the truth, then

you

realize there

is nothing to fear. What arises passes away, what is born dies,

and

is not self — so that our sense of being caught in an identity with this

human body fades out. We don’t see ourselves as some isolated,

alienated

entity lost in a mysterious and frightening universe. We don’t

feel

overwhelmed by it, trying to find a little piece of it that we can

grasp

and feel safe with, because we feel at peace with it. Then we

have

merged with the Truth. (Living Religions, 143)

How

might adopting the perspective of "interconnectedness"

(as opposed to "independence") change the way one experiences the world?

|

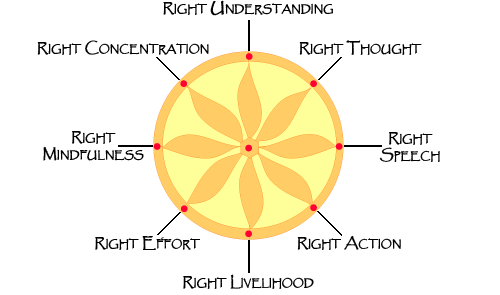

The path can be divided into 3 groups:

Wisdom

|

1. Right Understanding

Adherence to Buddha’s understanding of the Four Noble Truths as a

starting point.

2. Right Thought

Forming the

intention to pursue the Buddha’s path, including the

resolution to practice benevolence or “nonharmfulness” to sentient beings.

|

Morality

|

3. Right Speech

One’s

speech should always be in

accordance with the principle of “nonharmfulness.”

4. Right Action

One’s actions should always be in

accordance with the principle of “nonharmfulness.”

5. Right Livelihood

In line with the

previous ethical principles, laypeople should pursue a line of work

that

5. Right Livelihood

In line with the

previous ethical principles, laypeople should pursue a line of work

that

promotes the welfare of other sentient beings and minimizes

actions that might harm them.

|

Meditation

Meditation

|

6. Right Effort

The effort to

eliminate harmful karma at the mental level.

This represents the

beginning of

the self-examination process.

7. Right Mindfulness

Mindfulness

meditation employs aspects of the two main techniques of Buddhist meditation:

samatha (calming)

and vipassana (insight).

Samatha

is

good

for stabilizing the mind and preventing new karma,

but only “insight” leads to nirvana.

Mindfulness meditation

combines these by first stabilizing the mind by focusing on the breath

and then directing the mind to contemplate the nature of body, mind,

and their relationship to the totality of things.

8. Right Concentration

“Concentration” (samadhi)

builds on the practice of mindfulness by focusing on a particular

mental object until one

8. Right Concentration

“Concentration” (samadhi)

builds on the practice of mindfulness by focusing on a particular

mental object until one

reaches a state of “one-pointedness,” which in

turn leads to penetrating “insight” (vipassana) into the object of focus.

There is a traditional list of forty objects for meditative concentration,

ultimately leading to “formless meditations” (arupajhana) on mental objects such as

“nothingness” (sunyata) and “neither perception nor non-perception” (nevasanyanasanyayatana),

which are regarded as the highest states of consciousness that provide a glimpse into the nature of parinirvana —

the final release from samsara that occurs at the death of one who has fully awakened.

|

|

|