|

|

The

Buddhist theory of honji-suijaku

(“original substance manifests traces”) pervaded practically the whole of

Shinto. The theory of honji-suijaku,

transmitted from China to Japan, became

the theoretical foundation for considering Japanese kami as “manifest traces” (suijaku)

or counterparts of the “original substance” (honji) of particular Buddhas and bodhisattvas. For example, as early as the Nara period, Hachiman was considered both a kami and a bodhisattva without a clear distinction of Shinto or Buddhist

identity. In later periods almost every Shinto shrine considered its enshrined kami as the counterpart of some Buddha

or Buddhist divinity. It was customary to enshrine statues of these Buddhist

counterparts in Shinto shrines, and this practice further encouraged the

interaction of Buddhist and Shinto priests. (Japanese Religion, 120-1)

The honji suijaku theory was an extension of the idea that the universe

is really the activity of the Cosmic Buddha and that everything we think of as the cosmos is only the symbolic

expression of this activity. Hence all the various buddhas and bodhisattvas are

ultimately symbolic expressions, almost like emanations, of the single Cosmic

Buddha. For esoteric Buddhism, the “ground of reality” (honji) is Buddha-filled; but this ground has “traces” (suijaku) giving us the kami-filled world of Shinto belief. By

this reasoning, the various kami are

surface manifestations of buddhas existing on a deeper level of reality (which

are themselves emanating from the Cosmic Buddha).

The honji suijaku theory was, therefore, an explanation of how a

universal (Buddhist) reality could become localized as a Japanese (Shinto)

reality. This is fully in accord with the more traditional esoteric Buddhist

belief that the entire cosmos is the Cosmic Buddha and the world as we know it

is the manifestation of the activities of this Buddha. Esoteric Buddhists use

mandalas to portray how all buddhas emanate from the Cosmic Buddha (usually

considered Dainichi).

In accord with the honji

suijaku theory, so-called suijaku

art developed similar mandalas with kami

portrayed in place of the buddhas. This usually meant that Amaterasu replaced

Dainichi at the mandala’s center, suggesting in effect that all the kami emanated from her. In short:

esoteric Buddhist theory tended to fuse with traditional Shinto beliefs by

intellectually assimilating it, making it a manifestation — but only one

manifestation — within the broader Buddhist worldview. (Shinto: The Way Home, 98)

|

|

Born Shinto

Shinto for the Rituals of Life

In

the relationship between Shinto and Buddhism, the former typically

focuses on rituals associated with the living, while the latter is

closely associated with rituals for the dead.

Ofuda & Kamidana

Talismans for the Home Shrine

First Shrine Visit

|

|

|

Die Buddhist

Buddhism for the Rituals of Death

[During the Edo period (1600-1868)] every family was legally required to belong to a Buddhist temple

and had to be questioned periodically by the temple priest. “At one stroke, all

Japanese were incorporated administratively into the existing Buddhist

structure.” Births were registered and deaths were recorded in the local temple

to which the family belonged. ... The general situation tended to stifle religious

devotion, especially at parish Buddhist temples where family membership was

obligatory; temple members’ “relationship with Buddhism often came to be more

formalistic and pragmatic rather than a matter of individual religious

conviction.” The Japanese historian Anesaki has described the general

situation: “For the people at large religion was rather a matter of family

heritage and formal observance than a question of personal faith.” ... To the present day, the organized sects of Japanese Buddhism have not been able

to escape completely the unfavorable stigma of disinterested affiliation. Both

enlightened priests and devout laypeople have often deplored the inertia of

Tokugawa “feudal” patterns of Buddhist ancestor worship and have lamented the

lack of a strong, personal Buddhist faith in the setting of parish temples. (Japanese Religion, 146-7)

The death of a person

sets in motion a series of rites and ceremonies that culminates in the

observance of a final memorial service, most commonly on the

thirty-third or fiftieth anniversary of death. Between a person’s last

breath and the final prayers said on his behalf, his spirit is ritually

and symbolically purified and elevated; it passes gradually from the

stage of immediate association with the corpse, which is thought to be

both dangerous and polluting, to the moment when it loses its

individual identity and enters the realm of the generalized ancestral

spirits, essentially purified and benign. ...

An outstanding feature of the ceremonies

for the dead is that from start to finish they are primarily the

responsibility of the household and its members, for all of whom,

regardless of sex and of age at death, these same devotions will be

performed in some degree. Indeed, the longer the time since a person’s

death, the more likely that only household members will look after his

spirit. Many people will attend the funeral; fewer will attend the

rites of the forty-ninth day; and the number will dwindle over the

years as the memorial services are marked. The priest, too, has less

and less to do with rites for the deceased as time passes. It can be

said without exaggeration that the household members alone, through

their observance of the rites, prevent the ancestors from becoming

wandering spirits. ...

|

|

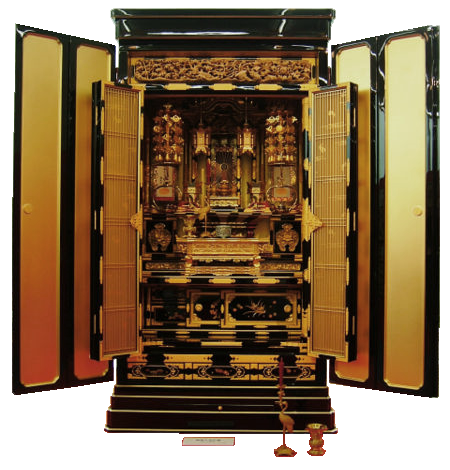

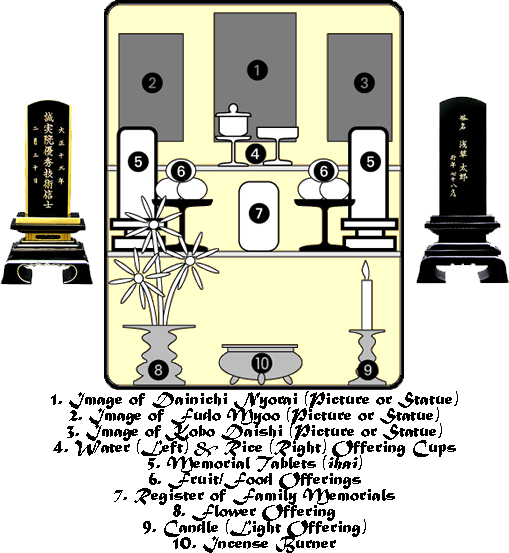

Haka Mairi and the Rites of O-Bon

Along with the butsudan the other great focus of unity and centre of ancestral rites is the haka,

the family grave, where usually ashes of all the family decesased are

interred. ... The grave is simultaneously a special place of contact

between the living and their ancestors, a receptacle for the spirits of

the ancestors, a site for ritual offerings to the dead and a symbol of

family continuity and belonging. ... The graves are usually in some

sanctified ground, such as within the precincts of the family temple

which thus oversees and protects the grave, with the priest conducting

occasional rites to this effect. But maintaining the grave properly is

the responsibility of the family and involves making offerings and

periodically cleaning it, and this is a vital aspect of the

relationship between the living and the dead, a means through which the

living may express their feelings for the dead and uphold the vital

balance and relationship through which the ancestors look after the

living. Failure to do this correctly may, just as with neglect of the butsudan,

invite problems: it is not infrequent for people who go to diviners or

to the new religions for help with personal problems such as illness to

be told that the cause of the problem lies in their failure to look

after the grave properly or that the grave has been badly sited and

requires changing. ...

The grave, then, continues to be a central element in all the rites surrounding death: in fact haka mairi remains

the single most widely performed religious activity in Japan, carried

out, as was mentioned in Chapter 1, by close to 90 per cent of all

Japanese people, young and old alike. It is primarily done at a number

of set times in the year, especially at higan (literally the ‘other shore’), the period around the spring and autumnal equinoxes, and the o-bon

festival in mid-July or August (the timing varies depending on the

region). Many families also visit their ancestors’ graves over the New

Year period as well. At these times it is customary to visit and clean

the graves, making offerings of food and drink to sustain the ancestors

in the other world and calling in a priest to read Buddhist prayers for

the benefit of the dead and to help them in their journey to full

enlightenment (the ‘other shore’ implied in the name higan). ...

The Bon Dance (bon odori) welcomes ancestors back to their graves and household altars ...

... and Buddhist priests are hired to perform memorial services on their behalf.

The most active and

demonstrative time for family unity and festivities connected with the

ancestors is the summer festive time of o-bon.

This is the period when the souls of the dead are considered to return

to earth to be with their living kin: since the ancestors are also felt

to reside in the ihai and to be encountered at the butsudan

throughout the year there are clearly some logical inconsistencies

here, but these appear of little relevance and are hardly ever

commented upon. (Religion in Contemporary Japan, 96-9) |

|

|

New Year’s Rituals

at Tsubaki Grand Shrine

|