In its earliest form, the people of a particular

region

established a symbiotic relationship with the powers of nature that

were

responsible for protecting the community. For example, since water

flows from the mountains to the fields, this natural cycle was

personified as a kami of the mountain (yama no kami) that descended in the spring to become the kami

of the field (ta no kami), which then returned to the mountain after the fall harvest. People therefore offered “first fruits” to this local kami

in order to ensure the protection of the community.

Otaue Matsuri (Rice Planting Festival)

Niiname Sai (First Taste Festival)

This idea of living in harmony with kami of the natural world is known as kannagara, which Yukitaka Yamamoto, ninety-sixth Chief Priest of the Tsubaki Grand Shrine, describes as follows:

| The Spirit of Great Nature may be a flower, may be the

beauty of the mountains, the pure snow, the soft rains or the gentle breeze. Kannagara means being in communion with these forms of beauty

and so with the highest level of experiences of life. When people

respond to the silent and provocative beauty of the natural order, they

are aware of kannagara. When they respond in life in a similar way, by

following ways “according to the kami,” they

are expressing kannagara in their lives. They are living according to

the natural flow of the universe and will benefit and develop by so

doing. (Living Religions, 226) |

|

|

Shinto & the State

The Birth of Japan

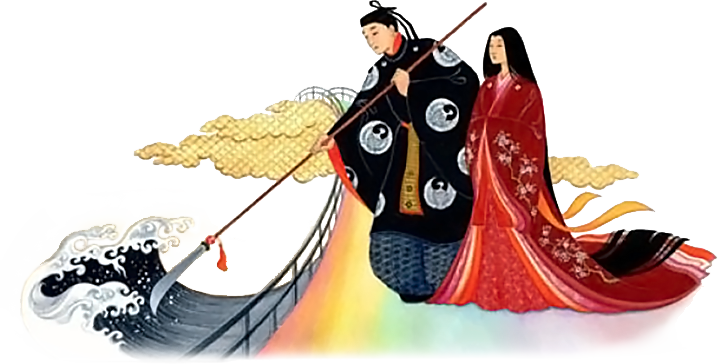

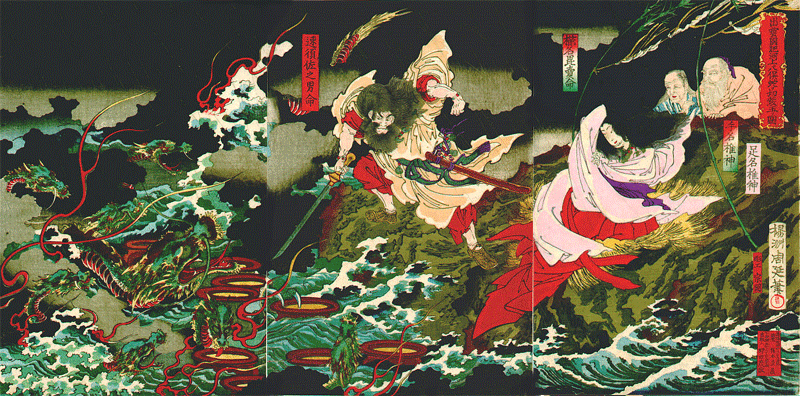

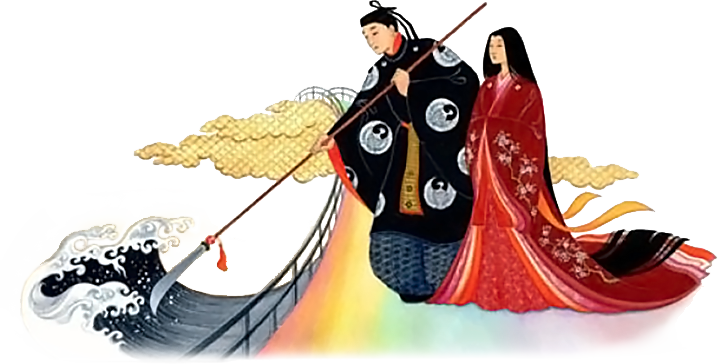

Izanagi

and Izanami stood on the floating

bridge

of Heaven and held counsel together, saying, “Is there not a country

beneath?” Thereupon they thrust down the jewel-spear of Heaven

and, groping about therewith,

found the ocean. The brine which dripped from the point of the

spear

coagulated and became an island which received the name of

Ono-goro-jima. The two deities thereupon descended and dwelt in this

island. (Sources of Japanese Tradition, 14)

How is this creation story similar to and/or different from

the more familiar account of "Genesis" in the bible?

|

|

Izanagi no Mikoto and Izanami no Mikoto

consulted

together saying, “We have now produced the great-eight-island country,

with

the mountains, rivers, herbs, and trees. Why should we not

produce

someone who shall be lord of the universe? They then together

produced

the Sun Goddess, who was called O-hiru-me no muchi. (Called in one

writing

Amaterasu no O-hiru-me no muchi.) The resplendent luster of this

child

shone throughout all the six quarters. Therefore the two deities

rejoiced

saying, “We have had many children, but none of them have been equal to

this

wondrous infant. She ought not to be kept long in this land, but

we

ought of our own accord to send her at once to Heaven and entrust to

her

the affairs of Heaven.” (Sources of Japanese Tradition, 20-1) |

[Izanagi and Izanami’s] next

child was Susa no o no

Mikoto. … This god had

a fierce temper

and was given to cruel acts. Moreover he made a practice of

continually

weeping and wailing. So he brought many of the people of the

land

to an untimely end. Again he caused green mountains to become

withered. Therefore the two gods, his parents, addressed Susa-no-o

no Mikoto,

saying,

“Thou art exceedingly wicked, and it is not meet that thou

shouldst

reign

over the world. Certainly thou must depart far away to the

Nether-land.” So they at length expelled him. (SJT,

20-1)

|

|

The Yasakani Magatama Jewels & Sacred Mirror

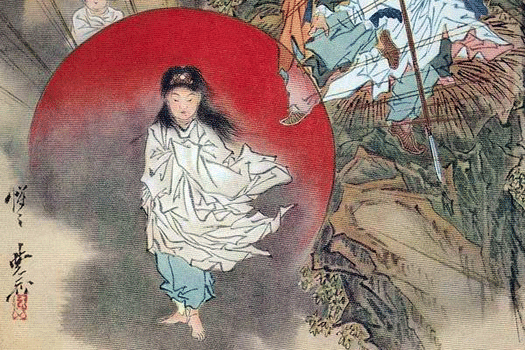

After this Susa-no-o no

Mikoto’s behavior was exceedingly rude. ... [For example,] when he

saw that Amaterasu was in her sacred weaving hall, engaged in weaving

garments of the gods, he flayed a piebald colt of Heaven and, breaking

a hold in the roof tiles of the hall, flung it in. Then Amaterasu

started with alarm and wounded herself with the shuttle. Indignant of

this, she

straightway entered the Rock-cave of Heaven and, having fastened the

Rock-door, dwelt there in seclusion. Therefore constant darkness

prevailed on all sides, and the alternation of night and day was

unknown.

Then the eighty myriad gods met on the bank of

the Tranquil River of Heaven and

considered in what manner they should

supplicate her. ... Then

Ame no Koyane no Mikoto ... and Futo-dama no Mikoto ... dug up a

five-hundred branched True Sakaki tree of the Heavenly Mount Kagu. On

its upper

branches they hung an august five-hundred string of Yasaka [Magatama] jewels. On

the middle branches they hung an eight-hand mirror. ...

Moreover Ame no Uzume no Mikoto,

ancestress of the Sarume

chieftain, took in her hand a spear wreathed with Eulalia grass and,

standing before the door of the Rock-cave of Heaven, skillfully

performed a mimic dance. She took, moreover, the true Sakaki tree

of the Heavenly Mount of Kagu and made of it a head-dress; she took

club-moss and made of it braces; she kindled fires; she placed a tub

bottom upwards and gave forth a divinely inspired utterance.

Now Amaterasu heard this and said, “Since I

have shut myself up in the Rock-cave, there ought surely to be

continual night in the Central Land of fertile reed-plains. How

then can Ame no Uzume no Mikoto be so jolly?” So

with her august hand, she opened for a narrow space the Rock-door

and peeped out. Then Ta-jikara-o no kami forthwith took Amaterasu

by the hand and led her out. Upon this the gods Nakatomi no Kami

and Imibe no Kami at once drew a limit by means of a bottom-tied

rope ... and begged her not to return again [into the cave]. (SJT, 24-25)

|

|

|

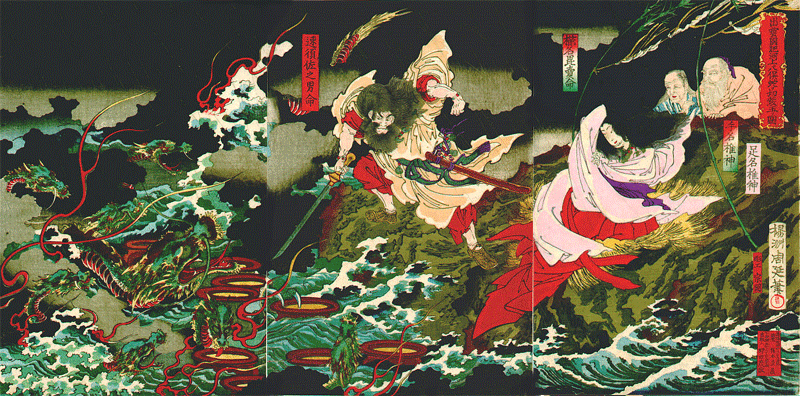

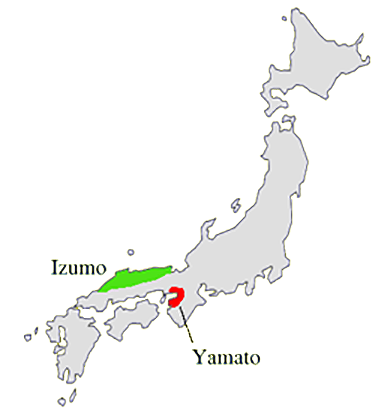

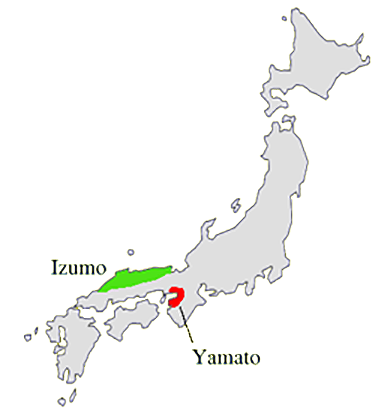

Susanoo

& the Great Sword

So,

having been expelled, Susa-no-o

descended to a

place [called]

Torikami

at the head-waters of the River Hi in the land of Izumo. [Susa-no

o met

an old male and an old female deity who were weeping because

they had

lost seven daughters to a serpent, which was now about

to take their eighth daughter. Susa-no

o then set out eight pots of sake (rice alcohol); when the serpent arrived, each of its eight heads drank a pot of sake so that it became intoxicated.]

Then

Susa-no

o drew the ten-grasp saber that was augustly girded on him and cut the

serpent in pieces, so that the River Hi flowed on changed into a river

of blood. So when he cut the middle tail,

the edge of his

august

sword broke. Then, thinking it strange, he thrust into and

split

[the flesh] with the point of his august sword and looked, and there

was

a sharp great sword [within]. So he took this great sword,

and

thinking

it a strange thing, he respectfully informed Amaterasu. This is the

Herb-quelling

Great Sword. (SJT, 25-7)

|

|

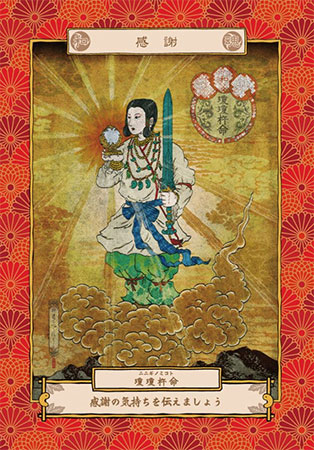

Ninigi & Jimmu

The Imperial Ancestors

After “all the Central Land of Reed-Plains” was

completely “tranquilized,” Amaterasu gave her grandson, Ninigi, the Three Treasures (a

curved jewel, a mirror, and a sword) and sent him down to rule the

earth, saying: “This ... Land

is the region which my descendants shall be lords of. Do thou, my

August Grandchild, proceed thither and govern it. Go! And may

prosperity attend thy dynasty,

and may it, like Heaven and Earth, endure for ever.” (Sources of Japanese Tradition, 28)

| According to tradition, Ninigi’s Great Grandson,

Jimmu,

went on to become the first “emperor” of Japan in 660 B.C.E. The

present emperor of Japan, Naruhito, is said to be a direct descendent of this

lineage, which is ultimately traced back to the kami Amaterasu. |

|

| In addition to the deities discussed above, the term kami refers to “the spirits that abide in and are worshipped

at the shrines. In principle human beings, birds, animals, trees,

plants, mountains, oceans — all may be kami. According to ancient

usage, whatever seemed strikingly impressive, possessed the quality of

excellence, or inspired a feeling of awe was called kami.” (Motoori Norinaga, quoted in The

Sacred Paths of the East, 247) |

Mt. Fuji, One of the Oldest and Most Venerated "Nature" Kami

Mt. Fuji, One of the Oldest and Most Venerated "Nature" Kami

Nachi Waterfall at the Kumano Nachi Shrine

The "Wedded Rocks" (Representing Izanagi and Izanami) at Futami no Ura

Sacred Tree With a Shimenawa (Rice-Stalk Rope to Ward Off Evil Spirits) Ise Grand Shrine, Dedicated to the Sun Goddess Amaterasu

Ise Grand Shrine, Dedicated to the Sun Goddess Amaterasu

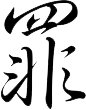

Impurity

Purification

|

In the traditions collectively referred to as Shinto or kannagara,

the world is beautiful and full of helpful spirits. ... However, ritual

impurity is a serious problem that obscures our originally pristine

nature; it may offend the kami and bring about calamities, such as

drought, famine, or war. The quality of impurity or misfortune is

called tsumi or kegare.

It can arise through contact with low-level spirits, negative energy

from corpses, negative vibrations from wicked minds, hostility toward

others or the environment, or natural catastrophes. In contrast to

repentance required by religions that emphasize the idea of human

sinfulness, tsumi

requires purification. The body and mind must be purified so that the

person can be connected with kami that are clearn, bright, right, and

straight. (Living Religions, 231) In the traditions collectively referred to as Shinto or kannagara,

the world is beautiful and full of helpful spirits. ... However, ritual

impurity is a serious problem that obscures our originally pristine

nature; it may offend the kami and bring about calamities, such as

drought, famine, or war. The quality of impurity or misfortune is

called tsumi or kegare.

It can arise through contact with low-level spirits, negative energy

from corpses, negative vibrations from wicked minds, hostility toward

others or the environment, or natural catastrophes. In contrast to

repentance required by religions that emphasize the idea of human

sinfulness, tsumi

requires purification. The body and mind must be purified so that the

person can be connected with kami that are clearn, bright, right, and

straight. (Living Religions, 231)

The

Western idea of sin generally involves intent; sin usually cannot be

accidental. The Shinto idea of defilement, by contrast, is more akin to

what we find in taboo cultures — that is, the contact itself is the

polluting factor regardless of whether the person knew about the

offense or undertook the action voluntarily. ... In the symbolic

language introduced in the previous chapter, we could say the

mirrorlike mindful heart is soiled (perhaps through no fault of its

own) and cannot reflect the kami-filled

world. Things will not go right from this point forward — the only

solution is a purification ritual to eradicate the pollution or

defilement. (SWH, 47-8)

What are the implications of focusing on "defilement" rather than "sin"?

|

Misogi (Ablution)

Harae/Oharai (Purification Rituals)

|

In the traditions collectively referred to as Shinto or kannagara,

the world is beautiful and full of helpful spirits. ... However, ritual

impurity is a serious problem that obscures our originally pristine

nature; it may offend the kami and bring about calamities, such as

drought, famine, or war. The quality of impurity or misfortune is

called tsumi or kegare.

It can arise through contact with low-level spirits, negative energy

from corpses, negative vibrations from wicked minds, hostility toward

others or the environment, or natural catastrophes. In contrast to

repentance required by religions that emphasize the idea of human

sinfulness, tsumi

requires purification. The body and mind must be purified so that the

person can be connected with kami that are clearn, bright, right, and

straight. (Living Religions, 231)

In the traditions collectively referred to as Shinto or kannagara,

the world is beautiful and full of helpful spirits. ... However, ritual

impurity is a serious problem that obscures our originally pristine

nature; it may offend the kami and bring about calamities, such as

drought, famine, or war. The quality of impurity or misfortune is

called tsumi or kegare.

It can arise through contact with low-level spirits, negative energy

from corpses, negative vibrations from wicked minds, hostility toward

others or the environment, or natural catastrophes. In contrast to

repentance required by religions that emphasize the idea of human

sinfulness, tsumi

requires purification. The body and mind must be purified so that the

person can be connected with kami that are clearn, bright, right, and

straight. (Living Religions, 231)