From Lao-Zhuang ...

... toHuang-Lao ...

... to the Celestial Masters!

... to the Celestial Masters!

Institutionalization

of ... ancient, esoteric, and popular practices into distinctive religious movements,

with revealed texts, detailed rituals, and priests serving as ritual

specialists, developed as the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) was

declining amidst famine and war. An array of revelations and prophecies

predicted the end of the age and finally led to the rise of

religious/political organizations.

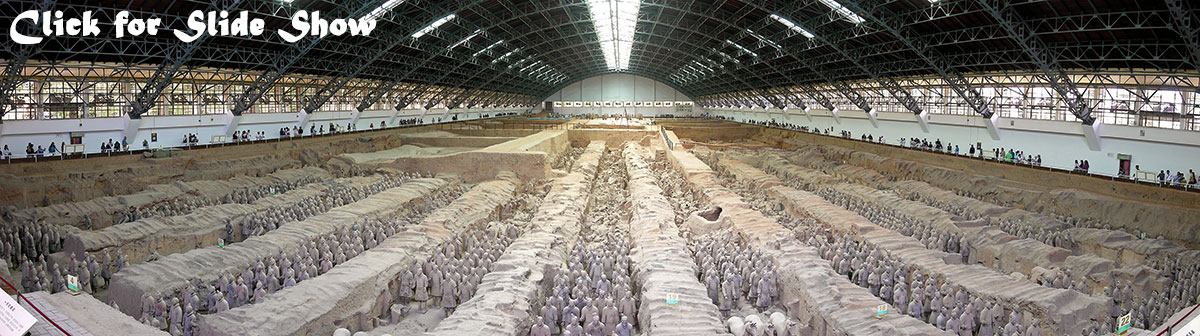

In 184 CE ... Zhang Daoling (Chang Tao-ling) had a vision in which he was appointed representative of the Dao on earth and given the title Celestial Master. He

advocated ... practices of healing by faith and developed a

quasi-military organization of religious officials, attracting numerous

followers. The older Han religion had involved demons

and exorcism, belief in an afterlife, and a god of destinies, who

granted fortune or misfortune based on heavenly records of good and bad

deeds. These roles were now ascribed to a pantheon of celestial

deities, who in turn were controlled by the new Celestial Master

priesthood led by Zhang’s family. This hereditary clergy performed

imperial investitures as well as village festivals, with both men and

women serving as libationers in local dioceses. After the sack of the

northern capitals early in the fourth century, the Celestial Masters

and other aristocrats fled south and established themselves on

Dragon-Tiger Mountain in southeast China. Today the Celestial Masters

tradition is thriving in Taiwan and Hong Kong, and the movement is also

being revived in mainland China. (Living Religions, 200)

|

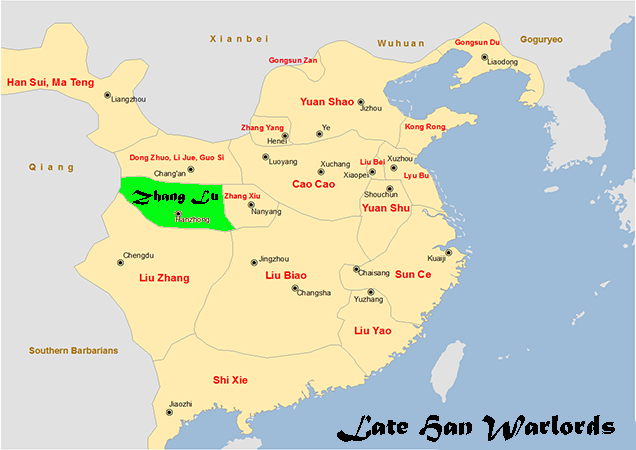

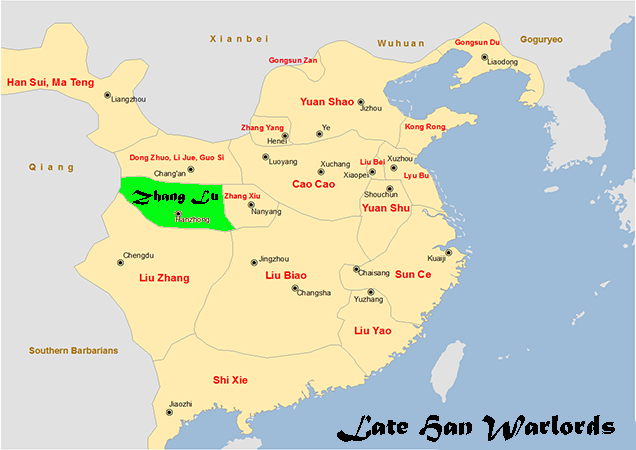

Under [Zhang Daoling’s grandson,

Zhang Lu], the Celestial Masters rose to greater prominence, notably

through merging with another local cult run by Zhang Xiu (not a

relation). This cult utilized a more stringent military-type

organization and practiced a formal ritual of confession and

petition — both characteristics that were to become typical of the

Celestial Masters in general. ... From what information we have it appears that

the followers of the Celestial Masters were hierarchically ranked on

the basis of ritual attainments, with the so-called libationers (jijiu)

at the top. They served as leaders of the twenty-four districts and

reported directly to the Celestial Master himself. Beneath them were

the demon soldiers (guizi),

meritorious leaders of householders who represented smaller units in

the organization. All leadership positions could be filled by either

men or women, Han Chinese or ethnic minorities. At the bottom were the

common followers, again organized and counted according to

households. Each of these had to pay the rice tax or its

equivalent in silk, paper,

brushes, ceramics, or handicrafts. In addition, each member, from

children on up, underwent formal initiations at regular intervals and

was equipped with a list of spirit generals for protection against

demons — 75 for an unmarried person and 150 for a married couple.

The list of spirit generals was called a register (lu) and was carried, together with protective talismans, in a piece of silk around the waist. (Daoism and Chinese Culture, 70-1) Under [Zhang Daoling’s grandson,

Zhang Lu], the Celestial Masters rose to greater prominence, notably

through merging with another local cult run by Zhang Xiu (not a

relation). This cult utilized a more stringent military-type

organization and practiced a formal ritual of confession and

petition — both characteristics that were to become typical of the

Celestial Masters in general. ... From what information we have it appears that

the followers of the Celestial Masters were hierarchically ranked on

the basis of ritual attainments, with the so-called libationers (jijiu)

at the top. They served as leaders of the twenty-four districts and

reported directly to the Celestial Master himself. Beneath them were

the demon soldiers (guizi),

meritorious leaders of householders who represented smaller units in

the organization. All leadership positions could be filled by either

men or women, Han Chinese or ethnic minorities. At the bottom were the

common followers, again organized and counted according to

households. Each of these had to pay the rice tax or its

equivalent in silk, paper,

brushes, ceramics, or handicrafts. In addition, each member, from

children on up, underwent formal initiations at regular intervals and

was equipped with a list of spirit generals for protection against

demons — 75 for an unmarried person and 150 for a married couple.

The list of spirit generals was called a register (lu) and was carried, together with protective talismans, in a piece of silk around the waist. (Daoism and Chinese Culture, 70-1) |

|

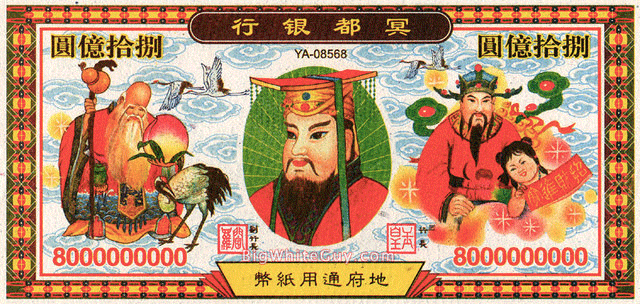

The families of the faithful were organized

into twenty-four parishes, led by priest-officials known as

libationers, who performed a combination of civil and religious

functions. An

important part of the libationers’ duties was their mediating between

the parishioners and the various gods and spirits. They also kept household registers

that were supposedly held by the gods of the celestial bureaucracy, who

watched over each individual and recorded his or her misdeeds. ...

Go up to Heaven to report (the family's) good deeds

Come down to earth to bestow good fortune (on us)

[The]

communication and supplication of the various celestial powers was

supposed to go via proper bureaucratic channels, with a priest

submitting a written petition to the appropriate celestial bureaucrat

in the same manner as a government official would present a memorial to

the court. The whole Celestial Masters movement was permeated with a

bureaucratic outlook that extended to the terrestrial and celestial

realms, which became a prominent feature of Daoism and popular

religion. (Introduction to Chinese Religion, 72-4)

|

|

|

Daoism in Contemporary Hong Kong

The Secret of Preserving Life

The Secret of Preserving Life

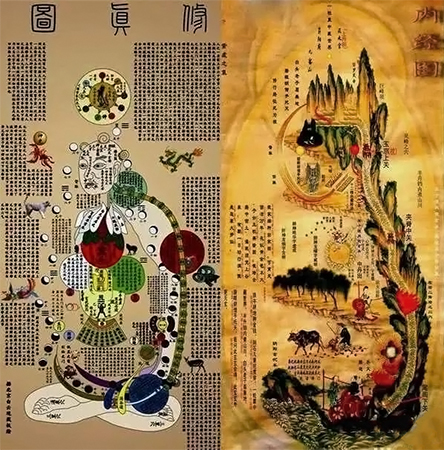

The

aim of the longevity practices is to use the energy available to the

body in order to become strong and healthy, and to intuitively

perceive the order of the universe. Within our body is the spiritual

micro-universe of the “three treasures” necessary for the preservation of life: generative force (jing), vital life force (qi), and spirit (shen).

These three are said to be activated with the help of various methods: breathing

techniques, vocalizations, vegetarian diets, gymnastics, absorption of solar and

lunar energies, sexual techniques, visualizations, and meditations. (Living Religions, 198-9)

I have heard that one who is good at taking

care of his life will not encounter wild bulls or tigers when traveling

by land, and will not [be wounded] by weapons when in the army. [In

this case] wild bulls will find no place in which to thrust their

horns, tigers no place in which to put their claws, and weapons no

place in which to insert their points. And why? Because in him there is

no place (literally, no ground) of death. (Chinese Religion, 81-2; cf. Daodejing 50)

Zhuangzi

Cook DingA good cook changes his knife once a

year — because

he cuts. A mediocre cook changes his knife once a month — because he hacks. I’ve had this knife of mine for

nineteen years and I’ve cut up thousands of oxen with it, and yet the

blade is as good

as though it had just come from the grindstone. There are spaces

between

the joints, and the blade of the knife has really no thickness. If

you insert what has no thickness into such spaces, then there’s plenty

of

room — more than enough for

the

blade to play about in. That’s why after nineteen years the blade

of

my knife is still as good as when it first came from the grindstone. ... “Excellent!”

said Lord

Wen-hui. “I have heard the words of Cook Ting and learned how to care for life!” (The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu, 50-51; cf. Zhuangzi, Chapter 3)

|

The

search for the elixir of immortality, closely related to, or identical

with “the philosopher’s stone,” apparently began in China and

eventually spread to the West. The alchemical elixir, when ingested,

would prolong life indefinitely; the alchemical philosopher’s stone

would be able to transmute base metals into gold. Gold was the common

denominator. In the case of the elixir, the symbolism of gold was that

of indestructible, incorruptible life. The hope of making cheaper

ingredients into the most valuable needs no symbolism. (Chinese Religion, 83)

The process of “inner alchemy” involves circulating and transmuting jing energy from the lower body into qi energy and then to shen energy to form what is called the Immortal Fetus, which an adept can reportedly raise

through the Heavenly Gate at the top of the head and thus leave their

physical body for various purposes, including preparation for life

after death. In addition, the adept learns to draw the qi of heaven and earth into the micro-universe of

the body, unifying and harmonizing inner and outer. (Living Religions, 199)

|

First take the power of heaven and earth and make

them into your crucible; Then isolate the essences of the sun and the moon: Urge the two things

to

return to the Tao of the center: Then work hard to attain the golden elixir — how

would it not

come forth? Secure your furnace, set up your crucible; always

follow

the power of heaven and earth. Forge their essence and refine their

innermost

power, always keeping well in control of your yin and yang souls.

Congealing

and dissolving, the incubating temperature produces transmutation. Never

discuss its mystery and wonder in idle conversation! ... Swallowing saliva and breathing exercises are

what

many

people do. Yet only with the method of this medicine can you truly

transform

life. If there is no true seed in the crucible, It is like taking water

and

fire and boiling an empty pot. ... “Empty the mind and fill the belly” — such

profundity of meaning! Just to empty your mind, you must know it first. Similarly,

to refine your lead, you must first fill the belly: Understand this to

protect

the mass of gold that fills your halls

within. (Anthology of Living Religions, 175-6)

|

The Disintegration of the Yin & Yang Souls

Beliefs

about the existence of supernatural or mysterious beings are based on

the notion that, at some level, the soul or spirit of a person can

survive the moment of physical death. Such conception of the soul and

the afterlife is grounded in ancient cosmological schemes central to

Chinese thought, which postulate fundamental order and unity in the

universe. Customarily, Chinese believe in the existence of two kinds of soul: earthly soul (po), linked with the yin element, and heavenly soul (hun), linked with the yang

element. Upon death the earthly soul — associated with darkness,

sensuality, and corporality — moves downward towards the earth and can

be transformed into a ghost. On the other hand, the heavenly

soul — associated with brightness, intelligence, and

spirituality — travels upwards and can be reborn as a god or an

ancestor. Despite their apparent differences, there are therefore

striking similarities between the ancestors and the gods, even though

the gods are believed to be in possession of greater numinous power,

and their influence purportedly extends beyond the confines of

individual families. It is also possible for an ancestor to transform

himself or herself into a god (but also into a demon). Accordingly, the

two classes of supernatural beings, gods and ancestors, are usually

worshiped in a similar manner. (Introducing Chinese Religions, 170)

Rituals for the Po (Yin) Soul

Rituals for the Hun (Yang) Soul

Rituals for the Hun (Yang) Soul

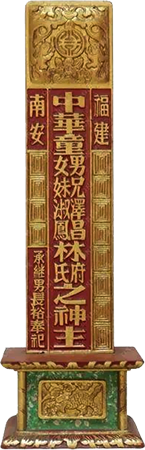

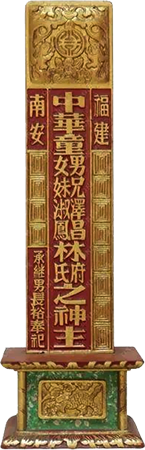

The

spirits of the ancestors are traditionally symbolized and commemorated

by means of ancestral tablets, on which their names are inscribed.

Within individual homes the ancestral tablets are placed at special

altars or shrines. In cases of wealthier households, there might be

separate ancestral halls, or even whole ancestral temples. Often

ancestral tablets are also placed at a local temple, which might be a

Buddhist or a Daoist establishment. Within the altar area the tablets

are frequently accompanied with statues or paintings of popular deities

such as Guandi, Mazu, or Guanyin. Offering incense and paying respects

at the ancestral shrine are integral parts of the domestic routine of

many Chinese households. On special occasions there are more elaborate

rites and sacrifices, which usually involve the offerings of food and

incense. (Introducing Chinese Religions, 170-1)

Spirit Tablets

Contemporary Family Altar

Contemporary Family Altar

|