Judaism,

like all modern religions, has struggled to meet the challenge of

secularization: the idealization of science, rationalism,

industrialization, and materialism. The response of the Orthodox has

been to stand by the Torah as the revealed word of God and the

Talmud as the legitimate oral law. Orthodox Jews feel that they are

bound by the traditional rabbinical halakhah,

as a way of achieving closeness to God. But within this framework there

are great individual differences [e.g. Ultra-Orthodox (Haredi), Modern-Orthodox, Hasidic, Chabad (Lubavitchers)], with no central authority figure or

governing body. (Living Religions, 291)

|

Laying Tefillin

Prayer Service

Keeping Kosher

Keeping Kosher

Kosher Certification

Kosher Certification

Torah, Talmud & Halacha

Torah, Talmud & Halacha

Studying Torah & Talmud

Studying Torah & Talmud

|

Orthodox Judaism on Netflix

|

The

Reform (or Liberal) movement, at the other end of the spectrum, began

in nineteenth-century Germany as an attempt to help

modern Jews appreciate their religion and find a place for it in

contemporary society, instead of regarding it as static and antiquatd.

In imitation of Christian

churches, synagogues were redefined as places for spiritual elevation,

with choirs added for effect, and the Sabbath service was shortened and

translated into the vernacular. The liturgy was also

changed to

eliminate references to the hope of return to Zion and animal

sacrifices in the Temple. Women and men were allowed to sit together in

the synagogue, in contrast to their traditional separation. Halakhic

observances were re-evaluated for

their relevance to modern needs, and Judaism was understood as an

evolving, open-ended religion rather than one fixed forever by the

Torah. (Living Religions, 292-3)

|

Bar Mitzvah Invitation

Bar Mitzvah Invitation

Bat Mitzvah Torah Portion

Bat Mitzvah Torah Portion

The

liberalization process has also given birth to other groups with

intermediate positions. With roots in mid-nineteenth-century Germany, Conservative Judaism seeks

to maintain, or conserve, traditional Jewish laws and practices while

also using modern means of historical scholarship, sponsoring critical

studies of Jewish texts from all periods. ... Conservative Jews believe

that Jews have always searched and added to their laws, liturgy, Midrash, and beliefs to keep them relevant and meaningful in changing times. Conservative women have long served as cantors and have been ordained as rabbis since 1985. (Living Religions, 293)

|

|

Rabbi

Mordecai Kaplan, an influential American thinker who died in

1983, branched off from Conservatism and founded a movement called Reconstructionism.

Kaplan held that the Enlightenment had changed everything and that

strong measures were needed to preserve Judaism in the face of

rationalism. Kaplan asserted that “as long as Jews adhered to the

traditional conception of the Torah as supernaturally revealed, they

would not be amenable to any constructive adjustment of Judaism that

was needed to render it viable in a non-Jewish environment.” ... Kaplan

created a new prayer book, deleting traditional portions he and others

found offensive, such as derogatory references to women and Gentiles,

references to physical resurrection of the body, and passages

describing God as rewarding or punishing Israel by manipulating natural

phenomena. (Living Religions, 293) |

|

In addition to those who are affiliated

with a religious movement, there are many Jews who identify themselves

as secular Jews, affirming their Jewish origins and maintaining

various Jewish cultural traditions while eschewing religious practice. (Living Religions, 293) |

|

The “Messianic Jewish identity” is wholly dependent on the person of

Yeshua: God Himself comes to earth to reconcile the Jewish people and

all nations to Himself. (See our Statement of Faith to find out more.)

“All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned every one to

his own way; and the LORD has laid on him the iniquity of us all.”

Isaiah 53:6

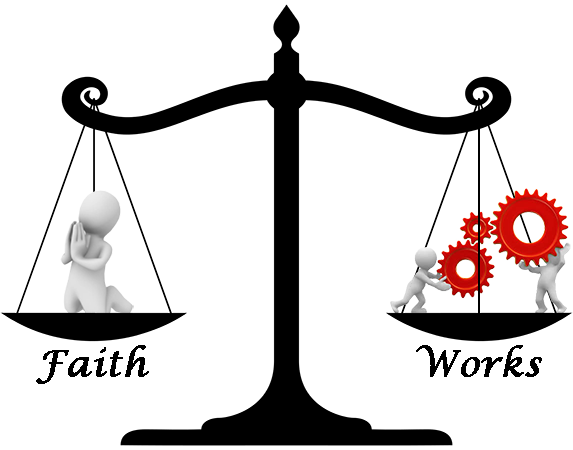

The foundation of Messianic Judaism, therefore, is each individual’s

personal relationship with the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob through

Messiah Yeshua. In the Hebrew Law God clearly demands a blood sacrifice

for the remittance of sins. Each Messianic Jew recognizes his or her own

sinfulness and has accepted that Yeshua Himself provided this

sacrifice.

Another important aspect of the Messianic Jewish movement is Jewish

congregational worship. If Yeshua really is the Jewish Messiah of whom

all the Jewish Law and Prophets spoke, then it is the most Jewish thing

in the world to follow Him!

Should Jews really attempt to assimilate into churches and forego

their Jewish identity when they choose to put their faith in the Jewish

Messiah? Messianic Judaism answers, “No!” As Yeshua Himself embraced His

Jewishness, Messianic Jews seek to embrace theirs, by meeting in

congregational communities with other Jewish believers and by

maintaining a Biblically Jewish expression of their faith. Every

congregation is different, but this expression often means worshiping in

Hebrew, following Mosaic Law, dancing as King David did before the

Lord, and keeping Biblical holidays such as Pesach, Sukkot, or Shavuot.

Also important is Messianic Judaism’s ministry to both the Jewish

community and the Christian body of believers. Messianic Jews are part

of the larger Body of Messiah throughout the world, and Messianic Jews

hope to help all believers in Yeshua to better understand the Jewish

roots of their faith. Finally, Yeshua declared that no-one can comes to

the Father – the God of Israel – except through Him (John 14:6).

Messianic Jews seek to share this way, this truth, and this life with

their Jewish brothers and sisters. (Messianic Jewish Alliance of America)

|

|